What does it mean to be an American citizen? We are experiencing “a crisis of national identity,” says Professor Samuel P. Huntington of Harvard University. In his book Who Are We?, Huntington notes that traditional American citizenship has Three Pillars: The English Language, Christianity, and British Customs.

What does it mean to be an American citizen? We are experiencing “a crisis of national identity,” says Professor Samuel P. Huntington of Harvard University. In his book Who Are We?, Huntington notes that traditional American citizenship has Three Pillars: The English Language, Christianity, and British Customs.

This four-part series from FPIW examines each — and the perils to them today:

• In Part 1, we focus on the impact of mass immigration as a threat to all Three Pillars.

• In Part 2, we support the First Pillar of the English language.

• In Part 3, we uphold the Second Pillar of Christianity.

• In Part 4, we honor the Third Pillar of our British roots, and then conclude with practical steps to strengthen American Identity.

🇺🇸 🇺🇸 🇺🇸

“We have not passed on what it means to be an American to this generation.”

– Dennis Prager

What does it mean to be an American?

For most of our history, American citizenship has been rooted in three pillars, says Professor Samuel P. Huntington of Harvard University. In his book Who Are We? The Challenges to America’s National Identity, Huntington highlights them as:

• The English Language

• Christianity

• British Customs

This four-part series of essays from FPIW will examine the importance of each pillar, respectively. Yet we first must begin here in this essay with another question: Why does “the crisis of national identity” exist in the first place? That is, what has threatened each of the three pillars?

The answer can be found largely in mass immigration.

I. Alien Nation: The 1965 Immigration Act

Like a tidal wave after tidal wave, tens of millions of immigrants have flooded into the United States since 1965. In fact, the mass immigration that Americans have experienced in the last six decades is unprecedented in world history: Never before have so many people moved into any country in such a short amount of time, explains Peter Brimelow.

Many Americans are concerned about the mass influx of illegals, drugs, terrorists, and violent criminals such as the MS-13 gang. But in addition to safety, a deeper concern is the loss of our culture, our shared American way of life, our home, what we “have, do, and think.”

Many Americans are concerned about the mass influx of illegals, drugs, terrorists, and violent criminals such as the MS-13 gang. But in addition to safety, a deeper concern is the loss of our culture, our shared American way of life, our home, what we “have, do, and think.”

They feel invaded: they are the ones who witness their religious traditions, heroes, heritage, music, symbols, language, dress, customs, and familiar neighborhoods get washed away when new immigrants flood in.

For years, all that was home is no longer home but a foreign land, an Alien Nation.

This profound shift is largely due to the impact of the Immigration & Nationality Act of 1965 signed by President Lyndon Johnson (see picture below). The Act is revolutionary, and may indeed be one of the most profound laws in all of American history.

It is profound in two ways: first, the location from where the immigrants originated, and then second the sheer increase in volume of immigrants. Before 1965, immigration favored immigrants from Northern and Western Europe, especially the British Isles. The logic was that the US should welcome people who are similar to the current culture and would more easily blend in, i.e., assimilate. But with the 1965 Act, immigration was essentially opened to people from all over the world, especially Asia and Latin America. (For statistical details on this shift, please see this link: Pew Research. For immigration rates since 1820, see the Statistical Yearbook of the Immigration and Naturalization Service (Table 1).)

In terms of volume, compare the difference:

In 104 years—from 1820 to 1924—only 34 million immigrants came, nearly all from Europe.

vs.

In only 60 years—from 1965 to 2025—more than 72 million immigrants came. The majority came from Latin America, some from Asia, the Middle East, Africa, and Europe.

Put more simply: “34 million in 104 years” vs. “72 million in 60 years.” Immigration expert Roy Beck comments, “It is the numerical equivalent of having relocated within our borders the entire present population of all Central American countries [Belize, Costa Rica, El Salvador, Guatemala, Honduras, Nicaragua, and Panama].”

Such mass immigration has engendered a cultural revolution and “a crisis of national identity.”

Kenneth Prewitt, former Director of the U.S. Census, concluded in 2001: “We’re on our way to becoming the first country in history that is literally made up of every part of the world.” Immigration scholar Jared Taylor notes that the United States has opened our borders to peoples from the four-corners of the earth and is importing “people who are as unlike each other as it’s possible to be.” With such volume as well as a shift in location, assimilation becomes quite difficult.

Recent immigration has engendered an American religious, racial, and linguistic transformation, and thus a cultural transformation consisting of conflict and making immigration a top political issue in recent elections.

II. “They Keep Coming”: Illegal Aliens

“What does it mean that your first act on entering a country—your first act on that soil—is the breaking of that country’s laws?” —Peggy Noonan, the famous speechwriter for President Reagan

The border between Mexico and the United States runs some 2,000-miles long. Often marked by steep rocks, a shallow river called the Rio Grande, or sometimes simply by a line in the dirt, this border has emerged as one of the most controversial issues in America in part because of illegals entering.

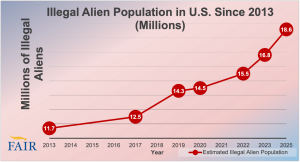

No one doubts the sheer mass of illegals, but the exact number has been a matter of sharp debate, since acquiring a precise number is difficult:

• During the early 2000s, people often used the figure of “11 million illegals” per the US Census, but many questioned its accuracy and suspected it was far too low.

• In 2005, a more in-depth analysis by Bear Sterns proclaimed 20 million illegals.

• In 2018, a Yale University study calculated 22 million, and postulated far more.

• In 2025, a report from the Federation for American Immigration Reform (FAIR) estimates there are 18.6 million illegals.

Regardless of the exact number, all agree that the wave of illegals into the US has been massive.

The 2004 groundbreaking cover story from Time magazine—“Who Left the Door Open?”—by two top-tier investigative journalists, sounded the alarm:

“The number of illegal aliens flooding into the U.S. this year will total 3 million—enough to fill 22,000 Boeing 737-700 airliners, or 60 flights every day for a year. No searches for weapons. No shoe removal. No photo-ID checks. Before long, many will obtain phony identification papers, including bogus Social Security numbers, to conceal their true identities and mask their unlawful presence.”

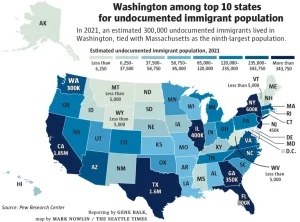

In Washington State alone, the current estimate is 300,000 illegals, which makes our state the 9th highest. But some suspect the actual number is exponentially greater:

III. Salad, Soup, or Wall: Three Views on Immigration

There are basically three views of immigration:

(1) Pluralists say, “Come as you are,” “Celebrate diversity,” “Our diversity is our strength,” and “We are a nation of immigrants.” They invite other races and religions in and believe they enrich the culture. Such a view is very popular among the ruling class in the U.S. (i.e., the media, entertainment, and educational systems). This view’s metaphor is a salad.

(2) Assimilationists say, “When in Rome, do as the Romans.” They believe man is malleable and can adjust to the cultural norms of the place to which he or she immigrates. They believe in a Melting Pot in order to “cook” each person into American culture. They believe that the U.S. is a nation of immigrants, but those immigrants must assimilate (or convert) into American culture, not keep their previous culture. The Assimilationists’ metaphor is soup.

(3) Exclusionists say, “All we ask is to be left alone. Time out on immigration. My neighborhood now feels like living in a foreign country. Mass immigration is a cultural weapon of mass destruction, and we are losing our history and culture. How would Mexico like it if 20 to 30 million Americans illegally invaded Mexico, demanded welfare, and kept living American culture rather than living like Mexicans?” Exclusionists resent being treated like rats in a social laboratory for a fake game of “Let’s all get along-ism.” Their symbol is the wall.

IV. Shattering the Common Core

For decades, social observers have been concerned about losing a common core. Dennis Prager writes:

But since the 1960s, the Left has supplanted e pluribus unum and its national American identity with the antithetical doctrines of diversity and multiculturalism. Diversity and multiculturalism celebrate the national/ethnic identities of the nations from where American immigrants came instead of celebrating the American identity and traditional American values. The result is the beginning of the end of the United States as we have known it since its inception. The Left constantly repeats “we are a nation of immigrants” without citing the other half of that fact—“who assimilate into America.” The Left mocks the once-universally held American belief in the Melting Pot. But the Melting Pot is the only way for a country composed of immigrants to build a cohesive society.

Note the early days of our nation. In 1787, as the United States was beginning, Founding Father John Jay wrote in Federalist No. 2 about his gratitude to God that Americans shared six common bonds:

Note the early days of our nation. In 1787, as the United States was beginning, Founding Father John Jay wrote in Federalist No. 2 about his gratitude to God that Americans shared six common bonds:

“Providence has been pleased to give this one connected country to one united people—a people [1] descended from the same ancestors, [2] speaking the same language, [3] professing the same religion, [4] attached to the same principles of government, [5] very similar in their manners and customs, and [6] who, by their joint counsels, arms, and efforts, fighting side by side throughout a long and bloody war, have nobly established their general liberty and independence.”

Consider the contrast to today by what Huntington wrote in the preface to his essay “The Hispanic Challenge” for the esteemed scholarly journal Foreign Policy:

“The persistent inflow of Hispanic immigrants threatens to divide the United States into two peoples, two cultures, and two languages. Unlike past immigrant groups, Mexicans and other Latinos have not assimilated into mainstream U.S. culture, forming instead their own political and linguistic enclaves—from Los Angeles to Miami—and rejecting the Anglo-Protestant values that built the American dream. The United States ignores this challenge at its peril.”

The concern is basically this: Do you want to be an American? People are coming into the nation—often illegally—and then living in their own enclaves, living as if they still lived in their original country, but accepting an American paycheck, not to mention receiving no small amount of welfare goods.

They are settlers, essentially building their own nation within a nation, and not converts who assimilate, as Huntington points out.

They live a segregated Mexican life: speaking their own language; reading their own literature and books; listening to their own radio stations and watching Mexican TV; and living according to Mexican holidays and customs. There is little American about them, and many Hispanics today do not refer to themselves as “Americans,” but prefer “Hispanic” or “Mexican”.

In fact, some Mexican immigration is not without a political agenda to la reconquista (a conquest to reclaim the land). Excelsior, the leading daily newspaper in Mexico, encourages the country to “recover its own”—due to losing land from the Mexican-American War (1846–1848), where Mexico surrendered much of the Southwest to the U.S. They believe the land is theirs.

In fact, some Mexican immigration is not without a political agenda to la reconquista (a conquest to reclaim the land). Excelsior, the leading daily newspaper in Mexico, encourages the country to “recover its own”—due to losing land from the Mexican-American War (1846–1848), where Mexico surrendered much of the Southwest to the U.S. They believe the land is theirs.

In contrast, older immigrants yearned to be Americans, Huntington says. Pre-1965 immigrants wanted to be Americans and make their lives part of the American story. Huntington quotes historians such as Oscar Handlin: “The newcomers were on the way toward being Americans before they stepped off the boat.” Adds Arthur Schlesinger, Jr.: these immigrants “yearned to become Americans. Their goals were escape, deliverance, assimilation.” And John Harles agrees: “[I]mmigrants are already faithful Americans when they first set foot on American soil. The process of assimilation … does not so much evangelize the pagan as it preaches to the converted.” These people were indeed converts.

V. Today’s Mission for Renewal

Huntington summarizes:

As a patriot, I am deeply concerned about the unity and strength of my country. … Americans should recommit themselves to the [British]-Protestant culture, traditions, and values that for three and a half centuries have been embraced by Americans of all races, ethnicities, and religions and that have been the source of their liberty, unity, power, prosperity, and moral leadership as a force for good in the world.

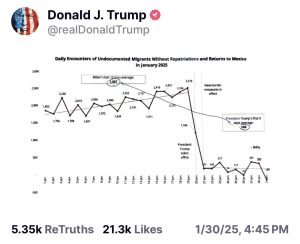

With the election of President Donald J. Trump, and his primacy upon controlling immigration, a renewal of American identity may begin, as the border crossings have decreased (see graph below) and many have self-deported:

But there has been violent pushback against the actions of Immigration and Customs Enforcement (ICE) with protests across the nation. The Mexican flag is often used as a symbol of protest, reports the New York Times:

Yet the mission for the renewal of American identity will continue, and this four-part series by FPIW aims to support such a mission. The identity crisis is real. The attacks against us are powerful. And so next, we turn to defending the First Pillar of American identity: the primacy of the English language.

#####

Additional Resources

American culture is important to us at FPIW, and we hope you share our sincere passion in defending and advancing Biblical and conservative values in the public square. Join us! Please sign up to become a Defender today, and join us in praying for our elected legislators.