What does it mean to be an American citizen? We are experiencing “a crisis of national identity,” says Professor Samuel P. Huntington of Harvard University. In his book Who Are We?, Huntington notes that traditional American citizenship has Three Pillars: The English Language, Christianity, and British Customs.

What does it mean to be an American citizen? We are experiencing “a crisis of national identity,” says Professor Samuel P. Huntington of Harvard University. In his book Who Are We?, Huntington notes that traditional American citizenship has Three Pillars: The English Language, Christianity, and British Customs.

This four-part series from FPIW examines each — and the perils to them today:

• In Part 1, we focus on the impact of mass immigration as a threat to all Three Pillars.

• In Part 2, we support the First Pillar of the English language.

• In Part 3, we uphold the Second Pillar of Christianity.

• In Part 4, we honor the Third Pillar of our British roots, and then conclude with practical steps to strengthen American Identity.

🇺🇸 🇺🇸 🇺🇸

“We are witnessing a reshaping of the nation’s linguistic identity.”

~ Prof. Ilan Stavans

Many of our older FPIW readers will no doubt remember a time in America when we:

• Did not hear “Press 1 for English … Press 2 for Spanish … ”

• Did not see signs and labels written in both English and Spanish

• Did not walk the neighborhood and hear people speaking in a foreign language

How times have changed.

“More than ever, modern America is multilingual,” reports the Washington Times. What a contrast:

• There are now more than 350 languages spoken across the nation.

• “The number of people who speak a language other than English at home has nearly tripled over the last three decades, increasing from 23.1 million to 67.8 million,” American Facts points out.

• USA Today reveals other non-English examples, including the US Citizenship Test: “People seeking to become U.S. citizens are also allowed to skip the English-language portion of the citizenship test or bring an interpreter, under certain circumstances.”

Those examples represent a growing threat to American Identity. A divided nation has many languages; a bifurcated nation has two languages; and a conquered nation changes its language—and so defending American Identity should include making English the official language. As Huntington notes: “Throughout American history, English has been central to American national identity,” and steps need to be taken to protect this First Pillar of American Identity.

I. President Trump’s Executive Order

Of all of his achievements so far in 2025, one of President Donald J. Trump’s most important may be related to our common national language: his defense of the English language. It is another campaign promise kept by way of Executive Order 14224. It has not received widespread press coverage, yet it’s absolutely critical. The EO says the official designation will create “a unified and cohesive society” with a “shared language” and will help new Americans assimilate. It states:

From the founding of our Republic, English has been used as our national language. Our Nation’s historic governing documents, including the Declaration of Independence and the Constitution, have all been written in English. It is therefore long past time that English is declared as the official language of the United States. A nationally designated language is at the core of a unified and cohesive society, and the United States is strengthened by a citizenry that can freely exchange ideas in one shared language.

His executive order said that designating English as the official language would streamline communication, “reinforce shared national values, and create a more cohesive and efficient society.” In addition to this EO, Trump ordered the Spanish version of the White House website taken down within hours of his Inauguration. He also signed another EO in April 2025 requiring truckers to be proficient in English.

As for the primary EO of making English the official language, Trump issued EO 14224 on March 1, 2025. It repealed President Clinton’s EO from 2000 that required the federal government to use other languages. Technically, de jure, the United States does not have an official language, but Trump’s EO is a support for a de facto protection of the English language, at least for government business. Symbolically and functionally, it matters and makes a difference. An EO, however, is not a reliable long-term solution because the next President could repeal it with the stroke of a pen. More protections are needed.

II. Why It Matters

Why does a common language matter? In a word: relationships.

Like clearing the land for ground upon which to build a neighborhood, a shared language is the foundation upon which a community can be built. It’s common ground: not only for the mechanics of a well-run society—such as road signs, voting, government documents, etc.—but for relationships, community, and building an “extended family” of neighbors and friends around us. Connections can more easily form.

For these reasons, language is often referred to as “the glue” of a cohesive society.

In fact, language itself is far more than mere noise or sounds. Its power is much more mysterious and spiritual: speaking a common language is “a spiritual transaction” between people, explains Prof. Peter J. Kreeft:

In fact, language itself is far more than mere noise or sounds. Its power is much more mysterious and spiritual: speaking a common language is “a spiritual transaction” between people, explains Prof. Peter J. Kreeft:

“It strikes people as strange today to say that language is an inherently sacred thing; yet this was the tradition of all ancient peoples. … Language is a soul-thing, not just a tongue-thing. It is a spiritual transaction. Our society is remarkably insensitive to the sacredness of language.”

Language is a key component in order to build healthy, strong relationships with depth, which of course is a key component to any lasting, successful society. Without a common language, communication is difficult or impossible, and thus building communities or nations often fails. Without a common language, Huntington writes, “America, in short, will lose its cultural and linguistic unity and become a bilingual, bicultural society like:

• Canada [French, English],

• Switzerland [German, French, Italian, Romansh], or

• Belgium [Dutch, French, German].”

In contrast, Japan, France, and Germany have helped to solidify themselves with a shared language.

III. The Linguistic Reshaping of Washington State

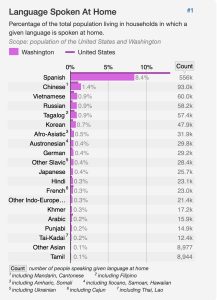

Although thirty-two states have enshrined English as their official language, Washington State has not. Here are some key points regarding language in Washington, which has a total population of more than 7 million:

• In homes across our state, there are some 20 different languages spoken; in total, that means there are more than 1 million foreign-language speakers, according to Statistical Atlas.

• Among those 20 foreign languages, Spanish is by far the most popular. Some 657,756 are Spanish speakers, calculates World Population Review. That is more than 8% in the state—with no signs of decreasing. Chinese is the second most.

• In Seattle, the 2025 City Council Resolution 32168 proclaimed: “Nearly one in five Seattle residents is foreign-born and 140 languages are spoken in Seattle’s public schools.”

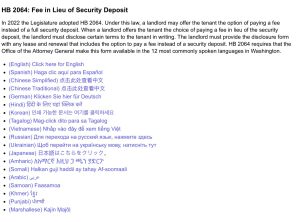

• The WA Attorney General and other government offices issue statements in 12 different languages:

• Washington State has been under fire for not enforcing the “English language proficiency requirements” in order to get a driver’s license and thus read road signs correctly. In 2025, an illegal alien killed 3 people in Florida when doing a U-turn with an 18-wheeler. He was charged with vehicular homicide, and his license was issued from Washington: “That driver couldn’t speak English and reportedly failed the Commercial Drivers License exam 10 times, but was issued a license anyway.”

IV. Hispanization: The Rise of Spanish

English’s status has come under attack in recent decades because of mass immigration.

More specifically, Spanish has grown to dominate regions of the nation. As explained in Part 1, since 1965, more than 72 million immigrants have entered into the United States, mostly from Latin America, and some from Asia, the Middle East, Africa, and Europe.

That tidal wave into our nation is unprecedented in world history in such a short amount of time.

The question now is one of bifurcation, as Prof. Samuel Huntington asks: “Should the United States become a bilingual society, with Spanish on an equal footing as English?” The trend in recent decades is toward “Yes.” Prof. Ilan Stavans points out: “You can open a bank account, get medical care, watch soap operas, file your taxes, love and die in America without a single word ‘en inglés’. In short, we are witnessing a reshaping of the nation’s linguistic identity.”

The question now is one of bifurcation, as Prof. Samuel Huntington asks: “Should the United States become a bilingual society, with Spanish on an equal footing as English?” The trend in recent decades is toward “Yes.” Prof. Ilan Stavans points out: “You can open a bank account, get medical care, watch soap operas, file your taxes, love and die in America without a single word ‘en inglés’. In short, we are witnessing a reshaping of the nation’s linguistic identity.”

Today, one will often see or hear Spanish in common places—street signs in two languages, food labels in two languages, political statements in two languages, at the grocery store, on mail in the letterbox, on billboards, at the ATM, and on airplanes during the safety video, for example. Virtually every national business phone service offers “Press 2 for Spanish…”

“The large and continuing influx of Hispanics threatens … the place of English as the only national language,” writes Huntington. The preface to his essay “The Hispanic Challenge” reads:

The persistent inflow of Hispanic immigrants threatens to divide the United States into two peoples, two cultures, and two languages. Unlike past immigrant groups, Mexicans and other Latinos have not assimilated into mainstream U.S. culture, forming instead their own political and linguistic enclaves—from Los Angeles to Miami—and rejecting the Anglo-Protestant values that built the American dream. The United States ignores this challenge at its peril.

Statistically, immigrants from Mexico (36%) and Central America (35%) have the lowest proficiency rates in speaking English.

V. Prominence of English in the United States

English is central to American identity. In 1787, as the United States was beginning, Founding Father John Jay wrote in Federalist No. 2 about his gratitude to God that Americans shared six common bonds, and one of them includes the common language of English:

Providence has been pleased to give this one connected country to one united people—a people:

[1] descended from the same ancestors [of Europe, especially Britain],

[2] speaking the same language,

[3] professing the same religion,

[4] attached to the same principles of government,

[5] very similar in their manners and customs, and

[6] who, by their joint counsels, arms, and efforts, fighting side by side throughout a long and bloody war [the American Revolution], have nobly established their general liberty and independence.

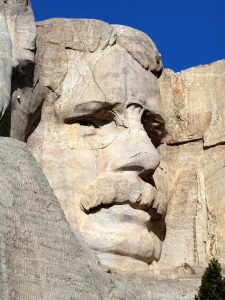

In the early 1900s, President Theodore Roosevelt continued to support the common language of English: “We must have but one flag. We must also have but one language. That must be the language of the Declaration of Independence, of Washington’s Farewell Address, of Lincoln’s Gettysburg speech and Second Inaugural.”

In the early 1900s, President Theodore Roosevelt continued to support the common language of English: “We must have but one flag. We must also have but one language. That must be the language of the Declaration of Independence, of Washington’s Farewell Address, of Lincoln’s Gettysburg speech and Second Inaugural.”

As Huntington says: “Until the appearance of large concentrations of Spanish-speaking immigrants in Miami and the Southwest, America was unique as a huge country of more than 200 million people virtually all speaking the same language.”

Such linguistic unity has been intentional, and it takes a team effort to preserve it.

VI. Americanizing: A Team Effort

“Teaching new immigrants English … has been a central concern of American governments, corporations, churches, and social welfare organizations,” says Huntington. As Justice Louis Brandeis said in 1919, an immigrant “substitutes for his mother tongue the English language.” This language requirement was part of Americanizing immigrants.

Here are just a few practical examples taken from Huntington’s more extensive research:

• The US Congress admitted new states only when they had a majority of English speakers.

• Henry Ford said of immigrants that “these men of many nations must be taught American ways, the English language, and the right way to live.” The Ford Motor Company required a six- to eight-month English language course for employees.

• Henry Ford said of immigrants that “these men of many nations must be taught American ways, the English language, and the right way to live.” The Ford Motor Company required a six- to eight-month English language course for employees.

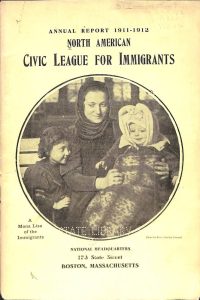

• Many organizations in the early 1900s Americanized immigrants, especially in the English language: YMCA, Sons of the American Revolution, Committee on Information for Aliens, and the Bard de Hirsh Fund, just to name a few.

• The government had an active role, too, notes Huntington: “By 1921, some 3,526 states, cities, towns, and communities were participating in Bureau of Naturalization programs.” The most important of which was the English language program.

• The project of Americanizing immigrants was profound: Between 1915 and 1922, more than 1 million immigrants enrolled in educational courses from the North American Civic League and the Federal Bureau of Education, among others.

• The project of Americanizing immigrants was profound: Between 1915 and 1922, more than 1 million immigrants enrolled in educational courses from the North American Civic League and the Federal Bureau of Education, among others.

“Americanization made immigration acceptable to Americans,” he sums up. Note the incredible and intentional efforts made by community organizations, big businesses, as well as the government. It was a team effort to Americanize.

In broad strokes, there are three historical linguistic eras:

(1) Early immigrants were mostly from the British Isles and spoke English.

(2) Just before WWI, the immigrants were more diverse linguistically, Huntington notes, including speakers of “Italian, Polish, Russian, Yiddish, English, German, and Swedish” — but who all basically came to speak English.

(3) But post-1965 Immigration Act, the immigrants were different: about half or more speak a single non-English language.

VII. Threats & Hope

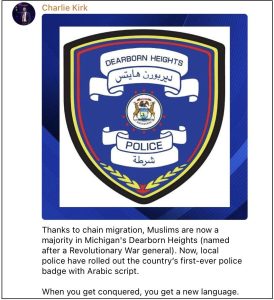

To attack a nation, you sever its roots, and the English language’s prominence in the US for hundreds of years has come under attack in recent decades, mostly from Spanish, but also from other languages such as Arabic—see above for the proposed 2025 Michigan police badge written in Arabic.

As Charlie Kirk says: “When you get conquered, you get a new language.”

As Charlie Kirk says: “When you get conquered, you get a new language.”

Deconstructionists—i.e., those who oppose the Three Pillars of American Identity—promote programs that refer to “peoples” rather than a single people of the United States (per the Constitution), and “they downgrade the centrality of English in American life … and push linguistic diversity,” emphasizes Huntington. They impose diversity—not community (unity)—as the greatest value of America. As President Bill Clinton said in 2000: “I very much hope that I’m the last President in American history who can’t speak Spanish.”

But our Founding Fathers knew better.

George Washington warned us—along with Thomas Jefferson, Ben Franklin, among many others—that if immigrants settled together, they would cluster into enclaves, form a nation within a nation, and “retain the language, habits, and principles (good or bad) which they bring with them.” Assimilation would not take place, and without assimilation, mass immigration becomes an invasion.

And that is in effect what has occurred.

But there is still time to reverse it. We can take steps to enforce English language proficiency as the First Pillar of American Identity, not only by national law, but also by way of local and state laws, as well as deporting illegals and halting all bilingual efforts. Linguistic American Identity matters, and we know progress will have been made when we no longer hear “Press 2 for Spanish…”, no longer see bilingual signs, and no longer have to ask our neighbors, “Do you speak English?”

Thanks in part to Trump’s EO, we now have momentum toward a “unified and cohesive society … strengthened by a citizenry that can freely exchange ideas in one shared language.” Or as President Theodore Roosevelt said a century before: “We must have but one flag. We must also have but one language.”

🇺🇸 🇺🇸 🇺🇸

In our next essay, we turn to the Second Pillar, what many consider to be “the heart” of American Identity: Christianity.

American culture is important to us at FPIW, and we hope you share our sincere passion in defending and advancing Biblical and conservative values in the public square. Join us! Please sign up to become a Defender today, and join us in praying for our elected legislators.